baristas I have loved

I was asked “Where do you feel most at home,” and what came into my mind (and then out of my mouth) was a cafe that I think I’ve only been to once, on a grey day in Paris twenty years ago, where I sat at a bench facing the large front window, drinking an Americano and noticing how many young, stylish women walking by were wearing knee-length black coats, wondering if that was a mark of style or constitutive of it, and tracing and retracing some Chinese characters on small-square graph paper for a short-lived interest in learning Chinese. Learning Chinese while living in Paris is a great illustration of how I’ve consistently substituted pursuing new interests for any mastery of existing interests.

Why that particular cafe settled into my mind in the way it did is probably irretrievable. It wasn’t the first time I’d noticed stylish young parisiennes, but perhaps I’d never before noticed that this group had identifiable features. Or maybe the coffee hit me just right. Or I was genuinely absorbed in learning the Chinese characters and noticed it. None of those guesses sound entirely plausible. I don’t remember going to that cafe again. The cafe probably wasn’t anything special, but it’s where my mind jumped.

It wasn’t surprising that a cafe is where I would feel at home, though. For one thing, there’s no obvious alternative, in the way that someone would have who grows up in a loving, calm house, feeling supported and that, no matter what else might happen anywhere else, that’s where he could always return. When I was in college, my parents moved from the second of the two houses I’d mostly grown up, but they had separated when I still lived there, and it was hardly a place of calm and support even before they separated. It wasn’t somewhere I wanted to go back to already by the time I went to college. I left at least a year too late for that.

Feeling at home in cafes is related to loving coffee, but it’s not the same. Coffee and cafes obviously arose together, since you can’t socialize over coffee without coffee. Cafes are more than that, though. I love the hypothesis that the spread of coffee through cafes in Europe might have led to the revolutions of the 18th century—or even earlier, given that King Charles II briefly outlawed them in 1675, shortly after the English Civil War, proclaiming:

Whereas it is most apparent that the multitude of coffee-houses of late years set up and kept within this Kingdom... and disaffected persons [drawn] to them, have produced very evil and dangerous effects; as well as for that many tradesmen and others, do therein mis-spend much of their time, which might and probably would otherwise be imployed in and about their Lawful callings and Affairs, but also, for that in such houses, and by occasion of the meetings of such persons, therein divers False, Malitious and Scandalous Reports are devised and spread abroad, to the Defamation of his Majesties Government, and to the Disturbance of the Peace and Quiet of the Realm; his Majesty hath thought it fit and necessary, that the Said Coffee-Houses be (for the future) Put down and Suppressed.

My own history with cafes led less to revolution than to having a place to hang out without alcohol. My love of coffee itself started well after getting to college. I didn’t drink coffee at all before that, and, in my first-year dorm room, I drank flavored, pre-ground filter coffee made in the Mr. Coffee when I needed to stay up late. Later that year, I visited my brother in grad school, and he informed me that what I thought of as fancy, gourmet coffee was decidedly not. (The Slate columnist Stephen Metcalf once memorably listed words whose presence suggested the opposite of their meaning, a group that definitely includes “fancy” and “gourmet.”) He had a wooden, pretty, very inefficient hand grinder, which was my first step towards understanding inefficiently made, good coffee. He said that coffee is approached first as a drink that needs lots of milk and sugar, but that, over time, you end up liking the flavor of the coffee itself. That wouldn’t explain the many coffee-flavored milk drinks served daily in cafes, but it was my path as well. (My dissertation advisor asked once if there are any acquired tastes that aren’t also addictive substances; there are, but it raises the great question of why anyone would keep consuming something long enough to acquire a taste.)

I didn’t drink alcohol much until late in college—by college standards of drinking, I never drank much, and that story is related to why my home didn’t feel like home, but that’s another topic entirely. I worked in a pub in London during the summer after my sophomore year, from which I returned with more comfort in bars and an early appreciation of beer, even if no more desire to drink. And, while I was as opposed to the high drinking age as everyone is until the day after they turn 21, I also didn’t like the fake-ID bars populated by drunk 19-year olds.

There was a cafe in my college town started by a recovered alcoholic who wanted a place that he could hang out with his friends when they wanted to drink, so this place served coffee from 6 am until 2 am. That’s where I found my place, first as a cafe, then as a bar. Over the next couple of years, I spent enough time sitting at that small, dark wood, heavily lacquered bar that the owner told me I deserved a plaque. I learned to love espresso in that cafe from people who knew the difference between good and bad espresso and were always happy to share that knowledge in a way that reminded you that you were decidedly less of an expert.

That bar, The Bourgeois Pig, is somewhere I visit when I’m back in Lawrence, Kansas, more for the familiar memories than for the (still excellent) espresso. But it’s been decades since I was there regularly, and the ownership is new, the baristas are new, they now don’t open until the middle of the day, and I don’t recognize anyone. When I left, it was Cheers, with a cast of regular employees and patrons, none of whom were interesting enough to carry a show, but whose familiarity together simulated friendship and made it worth my tuning in every day.

One of the guest starring semi-regulars moved away the year before I did, and I asked him if he was going to miss the place. He said no, that if he came back years later, he would find the same people doing the crossword and talking the same bullshit. From what I’ve seen stopping by since leaving, he was wrong about whether it would be literally the same people, but he was right that the people are in some other sense the same. They’re the same types, and so are the conversations. That guy—his name is long gone from my memory—was leaving to take a job in finance, and I lost touch with him even before he moved. I wonder if finance has the same people talking the same bullshit, or if he found a better cafe.

That cafe might also be where I had my first barista crush. I can only assume barista crushes are common, though I’ve never discussed them with anyone. They’re not regular crushes. They are superficially like bartender crushes, and they probably both come from the attractiveness of having someone who both serves you and is on display in doing so—and that person might have been hired because of how good they would be on display—but alcohol can induce crushes in most any context, and coffee doesn’t work that way. If coffee is an aphrodisiac, it’s in some headier way, though no less powerful for being easily rationalized as intellectual rather than visceral.

Karen was smart in the way that was somewhere closer to a trivia master than a philosopher. It seemed to my young self that, had her life around the university taken her closer to gown than town, the philosopher might have developed. I can’t even guess now how much of that is what I only wanted to believe. She was astute about what the customers wanted to see of her. (She once told me, through a brief crack in that facade, which of her pants led to the best tips.)

I would imagine that the skill of being a good barista, like anyone with a public persona, is learning how to seem like you’re letting people see the real you. Maybe not: the closest I’ve been is a waiter, but only for a short time when I was 16, and I was bad at it—not only did I not know what pants would get me the best tips, but I couldn’t have come up with a facade if I’d wanted to. (Or maybe that’s precisely what I’m trying to practice by writing about myself?)

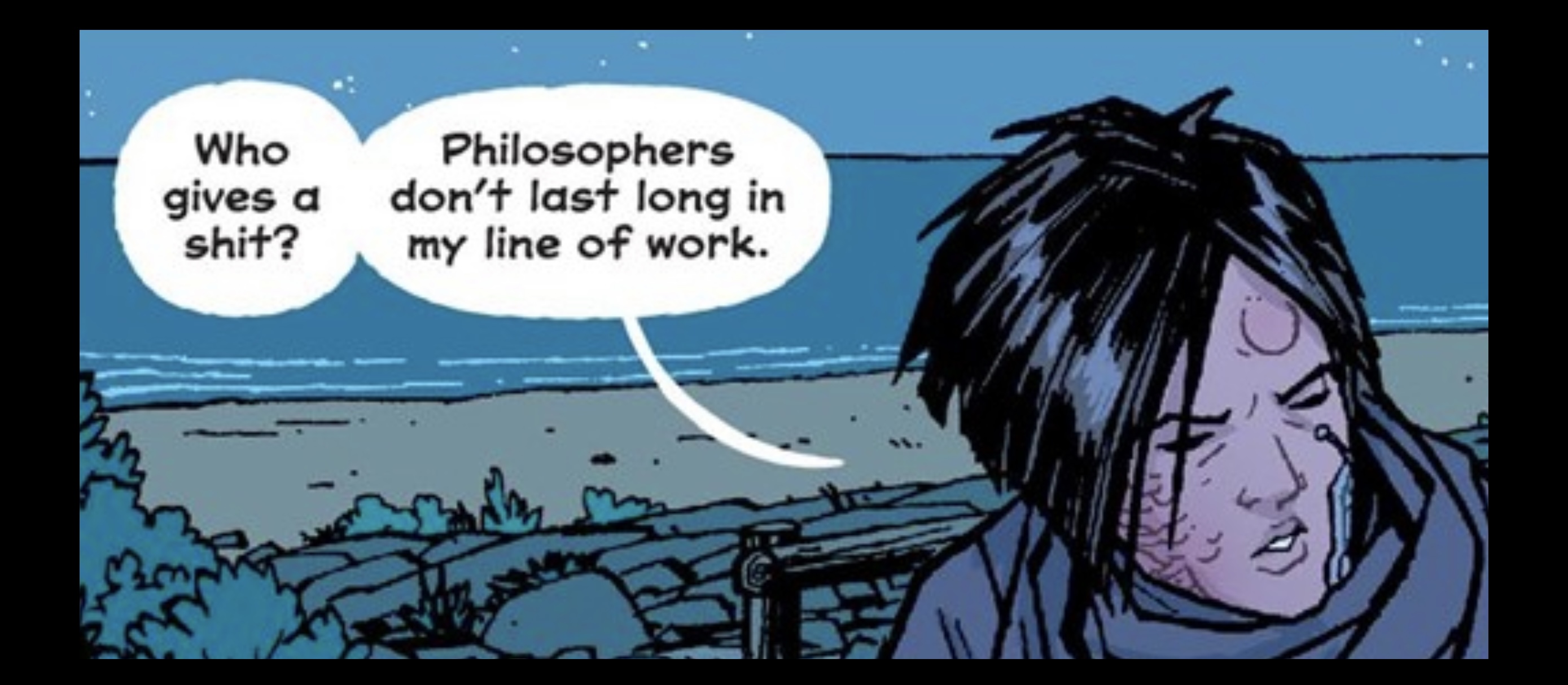

Facade or not, no one wants a real philosopher for a barista. (No one wants a real philosopher for anything, but they might not realize that.) Conversation with a barista is limited. At first, it’s nothing: they’re paid to be friendly, but not enough to have real conversations. Even if friendships and real conversation develop over time—and why couldn’t they?—it’s still conversation with a person who is in the middle of their job.

Philosophical conversation, by contrast, has to be sustained by an ongoing interest in figuring out answers that are not obvious (or not entirely obvious, anyway). Philosophical questions pop up however they pop up, and, while there’s a skill in recognizing a good question when it arises, and a good answer might be quick, but getting to a philosophical answer is annoyingly harder. The first answer might be exactly the right one, but you can’t know that until you’ve run down all the other paths. That’s philosophy. But how you can do that with interruptions and the divided focus of a person’s working at their job? A philosophical barista needs to be pithy, which is, at best, evidence that they could be philosophical if only they had time.

A barista crush, as I’ve had them, isn’t a regular crush in another way as well: they’re a crush within the context of the cafe. They are, at most, a reason to go to the cafe, a good feature, something to look forward to as part of good cafe, but not enough to make it worth going to a bad one. A friend once brought me along to a very sterile cafe, where the only good feature was a barista he clearly liked. That’s a regular crush, not a barista crush. I never asked him what he thought of the cafe, since that might have led to talking about how he felt about the wife who didn’t come with us, and I definitely wasn’t interested in that conversation. (The barista played no role in their divorce.)

Excellent coffee is enough to go to a cafe even if the ambiance is terrible (maybe the coffee is to-go). Comfy couches or interesting lighting or the right kind of dark wood or well-placed tables or outlets aren’t enough to go to the cafe, but they all work together to make the cafe worth going to. That’s where a barista crush is for me.

That wasn’t as true when I was younger, I’m pretty sure. These days, a memorable, friendly barista might be a barista crush when there’s nothing of a genuine crush there at all. When I was young, a barista crush was definitely closer to a crush. I wouldn’t have had a barista crush on someone whom I didn’t also find attractive. I was, however, either aware that the barista relationship is not to be sullied by hitting on the person, or it was obvious to my younger self that any barista I had a crush on wouldn’t spend time with me without being paid that I never tried. If I wasn’t going to be successful, I could at least be smug.

I’ll never know my motivations, though. Like Descartes going through various options to find something he can be certain of, I’ve tried to reconstruct what I was like when younger from the most secure and complete of my memories, and the occasional moment when a student reminds me of my younger self (usually in unflattering ways), but, ultimately, it’s too hard for me to know what I was like then. My psychological defense mechanisms were so strong then, and I doubt I encoded memories accurately enough that I could now mine them for information. If I could spend a day now with my young self, I’m certain I wouldn’t recognize him. I’m also certain I wouldn’t want to do that.

When I started writing this, I was thinking about the various baristas I have had barista crushes on over the years. They’re special memories, but some are from only fleeting interactions. Writing about them would be like making a stranger look at vacation photos. Or of the piles of junk that are taken from a person’s house when they die, things that were special when the person was still alive, but not because of the object itself. A rock that I picked up after napping on it on the Trinity College green in Dublin during a whirlwind trip from the summer bartending in London is still a rock, and it is nothing more than a rock when my memory of it is gone. The barista at Black Hole Coffee House who called me “dude,” gave me advice on cycling, and made my americano without my having to ask is special in my mind, but probably only as part of the decor of my memory of that part of my life. My memories of them might be memories of family filling my memories of home.