comics and poetry

learning how to read and why time isn’t spent

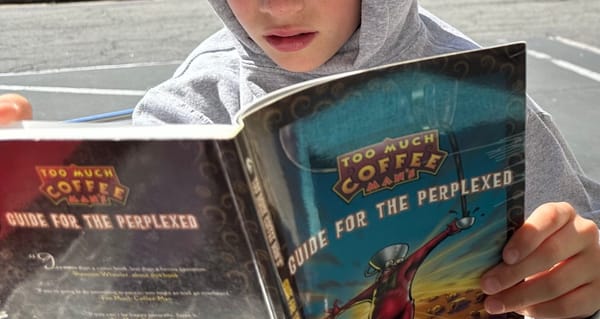

Comics have made me appreciate a way to read that I had completely missed in my previous four decades. I didn’t read comics as a kid and didn’t encourage my son to read comics either. But graphic novels are everywhere, and he was (and is) a voracious reader, so it was only a matter of time before his reading would include books with more pictures than words. When I realized that he had gotten into a couple of graphic novel series at school, I went with it—one of the hard things about being a parent is letting my son develop in his own way, regardless of what I might want. We started checking out the graphic novel section at the library when we were there.

Superheroes are also everywhere, and it was only a matter of time before he was learning all about DC and Marvel and their legions and teams and soap operatic histories and changes. Despite not being a comic kid myself, I still knew enough from a lifetime of being nerd-adjacent to explain quite a bit, and google filled in the gaps.

As he got older, and his books got more interesting, I started trying to read as much of what he read as I could. Not graphic novels at first, but eventually I was reading those, too. When we would travel to a place with a good comic store, we would ask for suggestions for new things for him to read. Some were good for him, and some were just good.

That all laid the groundwork so that when someone recommended Saga for me, I didn’t feel strange about picking up a graphic novel series for myself, without having him read it first. (I’m not sure at what age Saga is appropriate, but it’s certainly not 10, and maybe not 40 either.) That series was on a long hiatus when I read it, so I went to the local comic book store to start my first ever pull list, for that one single title, when it came back.

My son’s reading was getting more sophisticated, and I bought him the book Understanding Comics by Scott McCloud, which I read after he did, and it completely changed how I viewed this medium. Any person who enjoys reading and art should read it, but the take away was that I realized that I was reading comics all wrong. I was thinking of them as picture books, with art illustrating the story—and they can be that sometimes—when they’re an entirely different way of telling a story.

I’ll get to how that changed the way that I read in a second, because it actually didn’t change right away. What McCloud’s book gave me license to do was (1) separate superheroes from comic books, in a way that I’d done a little already but hadn’t really been clear about, and (2) give myself permission to read comic books in exactly the way I allow myself to read fiction. Which is to say, I like to read good fiction: interesting plot, nuanced characters, emotional resonances and/or intellectually engaging themes. I love Moby Dick, which has all of those. But I’m also finishing up Hench by Natalie Zina Walschots right now,1 which has the minimum of each of those, and it’s fun, too.

So, as I started looking into comics to add to this brand new, minimal pull list, I didn’t feel like I had to be sophisticated, but I did feel like I wanted to read things that were good. And the list grew, and I started talking to people in comics shops about what was good, and which writers were good, no longer only to buy things for my son, but now to buy things for me, too. I discovered an entire, enormous genre of literature that I had completely written off.

But here’s the thing that was amazing, that I’ve come to appreciate now that it’s been a year or so that I’ve been reading different series, sorting through titles and learning what I like and what I think works well in a comic format: I’m still trying to read comics too quickly. Mostly that’s because I’m still reading for the words and treating the art as illustration, though I now know better. But the bigger reason is because the stories that I’m reading—and I think this is actually true for comics as a medium, not just the particular titles I’m reading—have to be read much slower than I’m used to reading. The art of a panel is part of the panel, which is obvious, I know, but skimming the art is like skimming the words, except that I can get the gist of the art in a glance and the words I have to read over sequentially, even if I read them fast. So I can move quickly past the art and have to remind myself that I shouldn’t, whereas I have spent decades calibrating the speed of my reading to match what I want to get out of the words.

This is how comics remind me of poetry. When I was in college, a friend was taking an independent study on Ezra Pound’s Cantos. We were talking once about it, and it turned into a conversation about how to read poetry in general. I’ve never been a poetry reader: I probably read more comics as a kid than I have poems in my life (that don’t start with “Roses are…” or “There once was a man…”), and, as I said, I didn’t really read comics. What I realized in that conversation was that poetry is deceptive because it’s written out like a piece of prose, so you think you can read it the way you would any piece of prose, but it has to be read like looking at a painting.

Here’s what I mean by that. The philosopher of art Richard Wollheim wrote about looking at a painting:

I remember reading that passage almost 20 years ago and realizing I had never looked at almost any art like that. And, while I still mostly go through museums in the way I always have, I now also, when I’m on my own, find a piece to settle in front of for a while to enjoy the Wollheim experience. I don’t think I’ve ever sat for an hour—let alone for more than “the first hour or so”—but I have sat for a long time, long enough to appreciate what happens when you let your mind clear a little and let the art come in on its own terms. I’ve realized that parts of the painting don’t even appear to me until I’ve been letting it wash over me for quite a while. (In a painting at the Nasher museum, I discovered a person in the foreground of a painting I’d already been looking at for 5 minutes or so; it felt a little like I’d been standing in a room that I thought was empty and then heard someone clear their throat.)

That’s the image I have of how poetry is to be read. The words are easy to skim, just like a painting is easy to get the gist of. But, on the rare occasion that I’ve actually felt like I’m really reading poetry, it goes slowly, not necessarily in order, and part of the time I’m letting the words settle, trying to let my own ideas drift off so that whatever the poet is expressing can show up. It’s slow, and it’s so much slower precisely because there are few words relative to how much time I’ll have to spend on them, so, while it feels like I can read the poem at the speed of fiction, it’s actually closer to the speed of watching art.

Comics, then, I’ve come to realize have to be slow in that same way. It’s not because there’s art there, though that’s of course part of it. But the art of a comic panel is rarely at the level of the art of a painting in a museum. It’s not trying to be. But what it is trying to do is something that the painting is not: it’s telling part of a story. Not “telling a story” in some metaphorical way, like however an abstract painting is “telling a story,” or even the less abstract way in which Washington Crossing the Delaware is telling a story. It’s telling an actual story: plot, characters, stakes. And a lot of the story comes out by letting the art tell its own part of the story and not only be an illustration of whatever words are nearby.

This is obvious to anyone who reads comics, I’m sure, and I don’t understand comics deeply, so I’m not going to say more about how to read them. I know I don’t read them correctly, in general, because I can tell how much more I get out of them when I reread them. And reading them in a serial format, with issues every few weeks, introduces a whole other layer of reading, with lots of time to let each part of the story sink in or to see what details show up, or—as is most common for me—the need to reread issues before the new one comes out so that I can remember the details. I really love that extended way of reading and read lots of books in a similar way, with multiple books going simultaneously, one chapter every few days or even weeks.

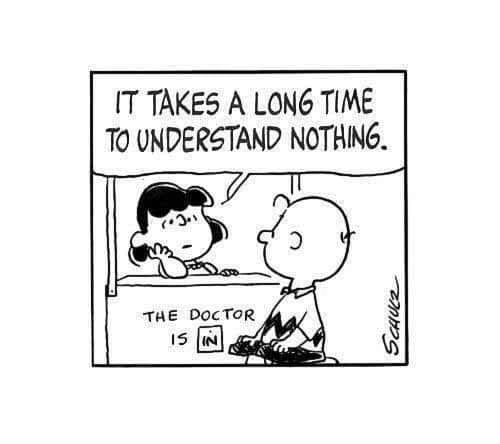

Here’s what I’ve come to appreciate in reading comics, and it’s probably what I would have come to appreciate if I’d read more poetry. If what I want is to have read a comic, I can do it quickly, even if it’s text heavy and with a convoluted plot. I’m a fast reader. But if I want to read the comic, it takes a long time, even if it’s a simple plot and straightforward dialogue. I’m trying to appreciate how long it took the artist to create each panel and to assume they had reasons for structuring it the way they did, and then to let that dictate the speed of reading.

And what this way of reading has made me start—but only start—to appreciate is the way I think about my time more generally. I want to read fiction and watch shows and movies and play games, and do all kinds of things that have nothing to do with advancing any goals I might have. I do appreciate that I don’t have to defend enjoying my life in those ways. But I still treat each of those things like I have to spend only the required amount of time on them. So, while I might read a comic, I can’t spend an hour letting a comic slowly reveal itself to me.

I’m reading a book on Idleness, by Brian O’Connor. I’d been thinking about how reading comics has reintroduced me to something I haven’t thought about much since trying to read poetry, and now this book is making me wonder if there’s something off about the entire way that I think about “spending” time. I understand why we think of it as a resource, and our lives are finite. And we have priorities, and I don’t think there’s anything wrong with wanting to accomplish some things. But I’m wondering about the importance of the things that we’re going to accomplish, rather than how we accomplish them. That’s abstract, but I guess I’m wondering if I should read a few comic books slowly instead of Moby Dick quickly. (Moby Dick really is good, though. I would reread it slowly. I read it once in high school and didn’t appreciate it and then again a few years ago and understood why people think it’s the Great American Novel.)

Maybe what I’m wondering is if the finite thing I should care about isn’t time but how much appreciation I can muster for any part of my life. It’s hard to appreciate much in my life, harder when I’m trying to do a lot. But what if I did less, much less, and really appreciated whatever few things I do? That is, what if I spent a long time writing out some thoughts on reading comics but really enjoyed thinking my own thoughts? Would that be part of a good life?

I’m going to write more about that later. There’s something really interesting about the way that the last couple of decades—more?—have been rehabilitating the bad guys. ↩