ethics for assholes

part 1, on rational reconstruction

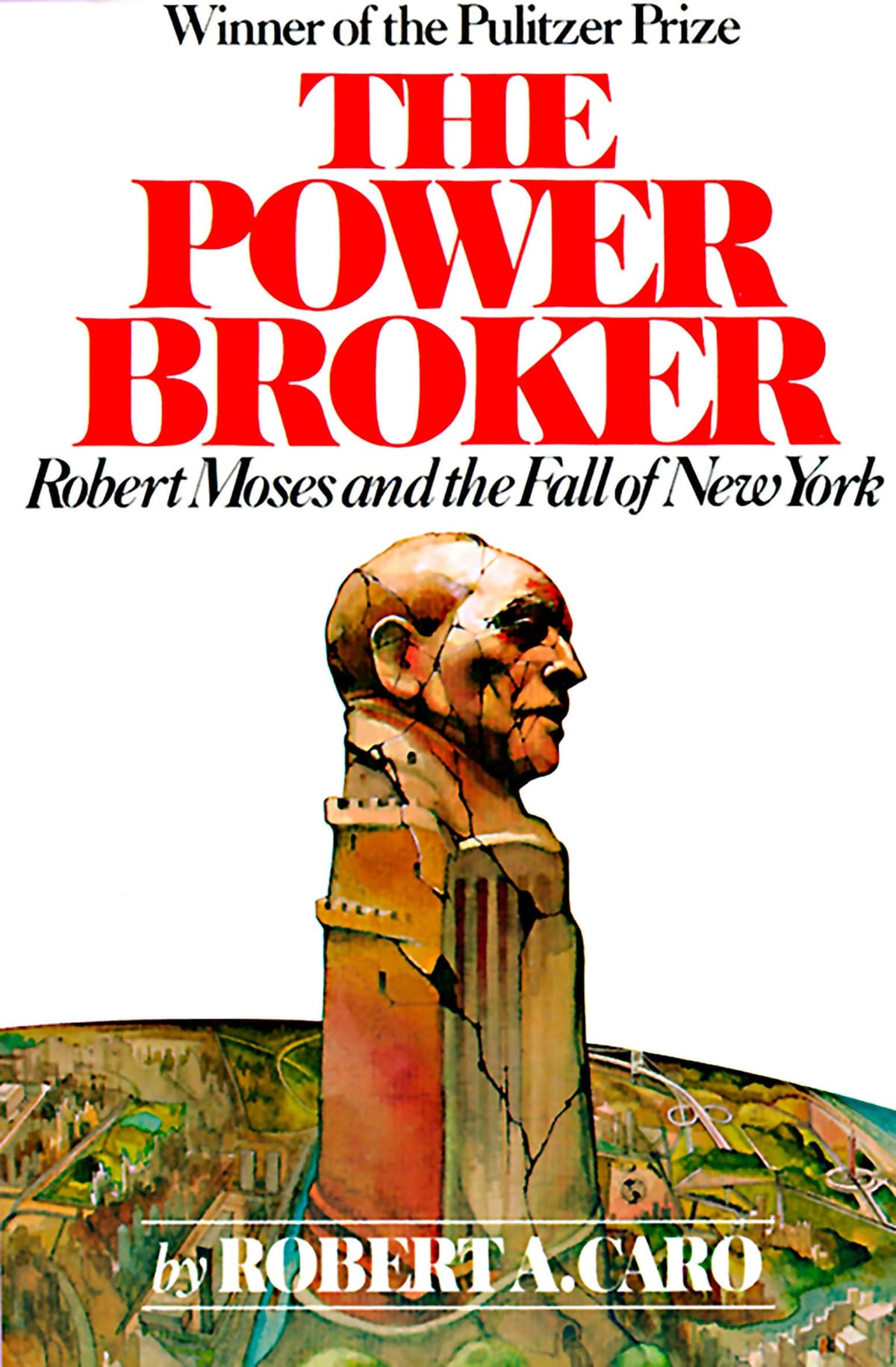

Aaron James proposes that assholes are something like narcissists: they see themselves as entitled to special treatment and insulate themselves from criticism. James’s proposal is a “rational reconstruction” of the word “asshole.” A rational reconstruction is a definition that is designed to be very close to what we ordinarily mean when we use a term, but it doesn’t worry about perfectly capturing every single way we use a term—the way a dictionary would—and instead tries to impose some coherence on the term so that it makes sense why all the cases that it does include fit together.

Rational reconstructions are what I remember coming up with while sitting around in The Bourgeois Pig as an undergrad, and it’s what I did in my dissertation, proposing a rational reconstruction of “addiction.” Rational reconstructions are fun, since there is often an underlying logic that we intuitively understand but can’t easily articulate in the words we understand and use all the time. (“Fun,” as used in the last sentence, is a great example; its underlying complexity is “fun” to figure out.1)

Rational reconstructions don’t replace dictionary definitions. Ordinary terms have rough edges, meanings that are only loosely or metaphorically connected to the main definitions. That’s part of the beauty of language, and one way that it changes as well, since what starts as an extension of the core meaning can become the central meaning. (“Fast” is probably my favorite example, but “like” as a verb is another good one.) A rational reconstruction, by smoothing out the term’s rough edges, isn’t a replacement for the dictionary definition and also isn’t the “real” definition. It’s a rational reconstruction: it illuminates the dictionary definitions, but is only a good reconstruction if it really does capture most of the dictionary definitions. (Theorists are sometimes divided into “lumpers” and “splitters”: lumpers want to combine as much as possible, and splitters want the opposite. Rational reconstruction is lumping; defending the variety of dictionary definitions is splitting. A single person can be both; only the lumpiest lumper would think otherwise.) So when James rationally reconstructs “asshole” to refer to a narcissist, his definition is illuminating, and it also doesn’t rule out the other ways we use the word.

The point of this writing isn’t to talk about rational reconstructions, though. The point is to talk about ethics. I often think about ethics and perfection, about how high our ethical standards should be and whether it’s ever ok to aim for less than perfection. (I think it is. I want to write a lot more about that.) But another way of thinking about the same topic is that, for some people, they’re not thinking at all about whether to aim for less than perfection. For them, they’re thinking about the minimum, or at least whatever the normal amount of ethics is. That’s what I mean by “assholes,” and they need ethics, too.

I don’t mean only that they need ethics in the sense that they’re less ethical, though that might be true. Someone who is thinking about whether they are required to strive for perfection isn’t normally an unethical person. They might do the wrong thing, but they’re very aware of trying to do the right thing, so much so that they’re wondering if it’s ok for them to do anything short of the absolute best thing at any moment. That kind of a person could certainly mess up ethically in a big way. Trying to be perfect doesn’t mean that your ideas are all correct, and the possibility of major error is there especially if your idea of perfection includes an ends-justify-the-means element in it. But at least they’re very actively trying.

But, for most people, ethical reasoning isn’t about trying to be perfect. For us assholes out here living our lives and hoping to avoid any major ethical catastrophes, we’re not immune to thinking about ethics, but it isn’t what we think about all the time. (I do, for professional reasons, but I still think of myself with this group, probably because there are limits to how sophisticated you can think of yourself as being when you grow up in a small town in Kansas.) We’re not assholes in the way that James rationally reconstructed the term. No, we’re assholes in the “just a bunch of regular assholes” way: ordinary people who aren’t trying to be bad, but aren’t necessarily trying to be good either. Ethically reasoning about how to be perfect isn’t what most people need. Thinking about whether to be perfect is a luxury. What most people need is a handy guide to ethical reasoning that doesn’t get in the way of thinking about everything else that makes for a good life. That’s what I’m going to write more to try to figure out.

A friend and I spent a recent dinner puzzling this one through. The question was why something like a shirt is called “fun.” Our reasoning went something like this. Some activities (parties, roller coasters) are fun, and those seem to be the core of the definition. Describing a venue, like a restaurant, as fun is then to say that it’s the kind of place where one is more likely to have fun. But what about my son’s pediatric dentist office? It’s decorated throughout with a vibrant underwater motif, and I would describe it as “fun,” but it’s not the kind of place that a person would have fun. Or a person’s shirt with an unexpected design? Or a nice design element on that shirt, like a fancy button? A button doesn’t lead to fun, no matter how fun it is. But our proposal (his proposal, really, but if I say who he is, there’s a chance the internet might somehow let him know, and then he might notice that I was writing here, and writing here is liberating precisely because no one is reading it; anyway, it’s mostly not my proposal) was that all these things are fun in that, relative to the kind of thing they are, they are conducive to fun. It’s like saying a “large gnat.” A pediatric dentist’s office isn’t conducive to fun, but, relative to pediatric dentists’ offices, the decoration of this one is conducive to fun. Buttons don’t lead to fun, but, relative to buttons, this fancy one is conducive to fun. Even the fun restaurant is best understood this way: the restaurant is fun in the sense that it’s conducive to fun, relative to a restaurant, so it’s less fun than a party or a roller coaster, but more fun than, say, a cafeteria. That’s the proposal. (If I were to keep thinking about this rational reconstruction, I would have to ask why a school cafeteria, which in fact is more conducive to fun than the most fun adult restaurants I’ve been to, wouldn’t be described as “fun.”) ↩