how to regret

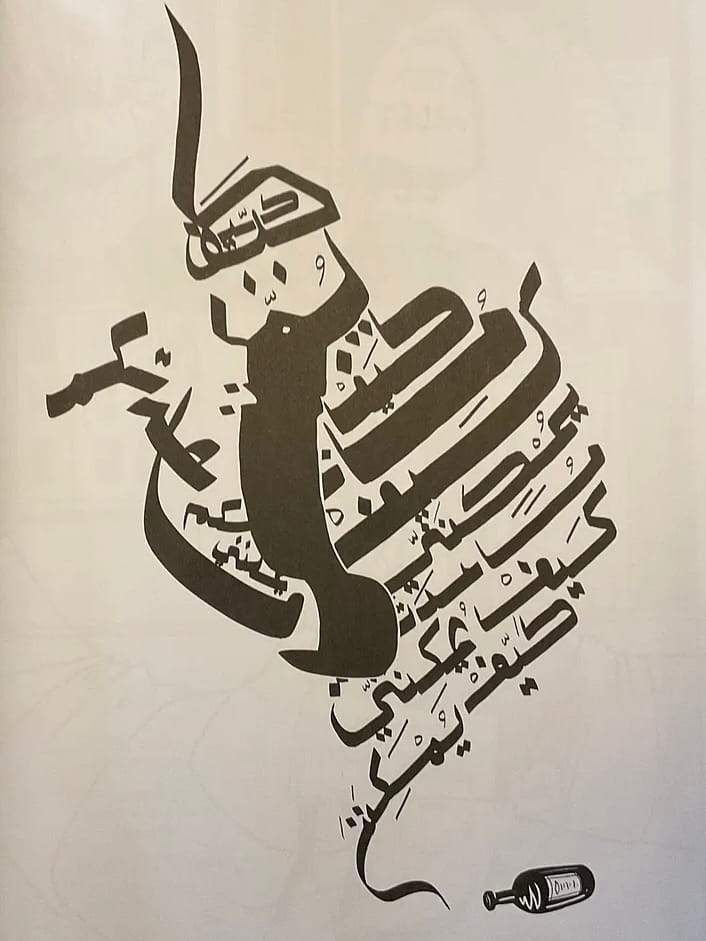

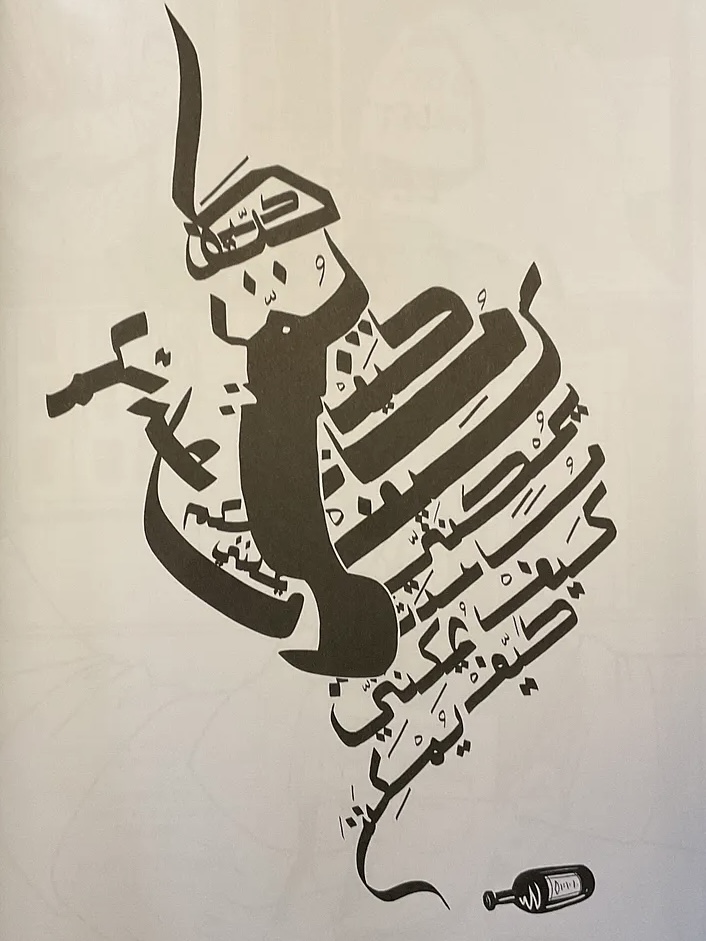

I just finished reading Shubeik Lubeik, a graphic novel from the Egyptian writer and artist Deena Mohamed. It’s a wonderful imagining of a modern Egypt in which wishes are bought, sold, regulated, and used.

One of my favorite parts of the book focuses on a regret, on undoing the past. Almost every semester, the topic of regret comes up with my students. There are two features of regret that make it interesting to me because they seem to conflict.

First, we use anticipated regret—will I later regret this?—as a test for whether we should do something now. I’m not sure what to do, but I don’t want to regret not doing this, so I will.

Second, we think that regrets are bad, maybe even that a good life would be one without regrets. But a regret seems to entail that if we had a way to do things over again, we would do them differently. But I suspect, for many people and many regrets, we in fact wouldn’t redo the past even if we could because redoing the past would change too much we love about the present.

That second position—we wouldn’t in fact change what we regret—makes it strange that we worry now about possible future regrets, since, presumably, what’s true of past regrets will be true of future ones: even if we someday regret what we’re about to do, we wouldn’t be willing to go back to this decision to change it.

That’s probably confusing, so here’s a very concrete example. One of the most influential decisions I ever made was to go to the University of Kansas. I’m from a very small town in Kansas with parents who hadn’t finished college, and, in the days before the internet, I didn’t know anything about college. I didn’t even plan on going to college until I was probably a junior. I also wasn’t into college sports, so the one entry point to thinking about college that I could have had wasn’t there. I knew of Harvard and Yale, of course, and I remember not being sure if Princeton was a college. I knew states had colleges, and I knew of three or four colleges in Kansas, and I thought that KU was the best one. The one pre-college conversation I had with a college counselor was when he asked me where I was thinking of going to college, I said “KU,” and he, with a cardboard jayhawk standing on his desk, said that seemed like a good choice.

In many ways, it was a good choice. I had a good education, a much better one than I could appreciate at the time. My majors had small courses, and most of my non-major courses were in the honors program, which meant I had almost entirely small seminars with faculty. I got a good scholarship and additional money to live abroad for a year in Paris while I was there. I explored my interests, finished 4 majors, worked closely with lots of faculty, and wrote a couple of (probably mediocre) honors theses.

I had good friends, whom I drifted from afterwards—I’m still not sure how much that was on me and how much that was a reflection of how I changed throughout undergrad and afterwards; maybe both. (I regret that, too, but that’s another topic.) I enjoyed my time socially, defined myself in opposition to the partying greek scene and hung out with nerdier types who thought of ourselves as cooler than that, though the partying greek scene certainly didn’t feel my absence. I drank a tremendous amount of increasingly good coffee at cafes around town, read a lot, bullshitted way more, spent money I wouldn’t earn until years later, and turned from a kid straight out of a rural town of 7000 people into someone who, in dim enough lighting and without asking probing questions, could plausibly pass for somewhat sophisticated. It was almost a model of what an undergraduate education should do.

Now, to set up the regret. I had skipped 8th and 11th grades and got a 34/36 on my ACT when I was a sophomore. I had had an interesting background, which I didn’t appreciate since it wasn’t interesting to me. I thought I didn’t have enough language courses to apply to Yale, and I’m sure I was too intimidated to apply to Harvard regardless of whatever their application criteria were. I didn’t know about the dozens and dozens of top places I might have loved, and I certainly didn’t know enough to know that I had potentially a very strong application. I also had no idea that I would have found other schools and experiences even more interesting, certainly more challenging. So I didn’t apply.

So the regret is this. Because I didn’t apply anywhere else, I went to KU, where I had a good experience and where I also decided to go into higher ed (also thanks to a program I found as an undergrad—I wonder if I would have made that decision regardless). But KU doesn’t open doors in higher ed in the way that a top university or a top philosophy department at least would have. I then went into a field that (unofficially, and with some justification) cares deeply about where a person went to school. So I regret that I didn’t go to—or at least apply to—any top universities, ones that would have given me a chance to have had a good career in higher ed or perhaps in something even more rewarding, to have challenged me more and earlier, and whose faculty would have been well connected. Dozens of universities would have helped me. Some of that help would be in ways that I would never have been able to identify; but, after decades hearing people refer to a person’s undergraduate institution to describe them, I’m certain that help would have been there, but it’s not in my case.

That’s the regret. It’s a real regret. It hurts, and it hurts pretty strongly at times. I wish I’d been able to have the life that branched off from the decision to apply to other schools, to have had those challenges, made those friendships, to have had those professors, to see where those connections took me. I will probably never recover from the realization, which dawned over years, of how hard it would be in higher ed for me to overcome a barrier I erected myself by not learning about some other colleges in time to apply to them. This is not a fight against prejudice: my undergraduate education, as good as it was, prepared me less for this career, the one that I am close enough to see and envy, but have drifted further and further from every year. The lack of a top-college credential is a shorthand way of pointing to a less challenging undergraduate experience, and there is certainly some prejudice bundled into what it takes to get into and succeed in a top undergraduate institution, but it’s not entirely prejudice.

And yet, if I had a magic wish and could change that one part of my life, I couldn’t do it. That decision didn’t bring me to the life I could have had, to the life I now envy, and it certainly didn’t make things easy. But I’m also now in a comfortable room in a good neighborhood, writing about regret just for my own intellectual curiosity, before I leave with my wife to go to my son’s good school for his parent-teacher conferences. All of us are, now, in good health. These are good years for us: they could be better, but not in ways that I regularly think about. I don’t think this is uncommon; rationalization or adaptation, humans are generally good at being more or less satisfied with the position that we’re in, whatever it is.

The likely ceiling for the path I took when I went to KU and then went into higher ed was not especially high, and I might have come close to it. To do it over again, I would be rolling the dice to try for something higher. I couldn’t risk it. I’m too risk averse, but, more importantly, I’m also too attached to the particular things that came in this life. I might love a different house and a different city even more: I can imagine that. Maybe I would have a wife I loved more and a son I was even happier with, but it’s hard even to know how to imagine that: loved ones aren’t interchangeable like that, and “love even more” suggests a comparison we might not be able to make. (In the book of Job, after losing his wife and children and everything else, Job gets a new wife and has new kids. Is the new family supposed to reassure the reader that everything is fine, now?) Someone in my own 16-year-old position should apply to top schools, but I don’t think, with a djinn in a bottle, I could act on my own regret to undo my decision.

To say that I will regret a decision is to say both that I think it’s a bad decision, and that I think time will only confirm that. (By contrast, I could be worried about a decision but think on balance I’ll be happy later that I’ve done it.) Deciding based on anticipated regret then seems to hold together two ideas: the first is that the decision is bad, regardless of the outcome; the second is that the outcome will also be bad, regardless of the decision. I won’t regret spending my rent money on lottery tickets if I win the jackpot, even if it was a bad decision. And I might regret calling “heads” on a coin flip to win $100, but there was nothing wrong with the decision itself even if the coin turns up tails. And I might regret my college decision even if the outcome is a life I wouldn’t take a chance on changing.

Kathryn Schulz proposed that regrets are valuable. Her argument for it has to do with the forward-looking value of having regrets, that regrets teach us about what’s important and help us live a good life. It feels like the common argument that failure is good because you can learn from failure: it might be true, but you can also learn without failing. You can also know what you care about without the pain of regrets. So regrets and failures are normal parts of a normal life, and they have benefits, but that’s different from saying that they’re themselves valuable.

There is a path to Schulz’s stated conclusion that regrets are themselves valuable, though, by arguing that a good life is one in which good things happen and other good things could have happened, and you would rather keep your regret than do things over again. I wouldn’t trade in my regret about my college decision for a chance to do things differently because this life is good, and that life might be worse overall, and, even it’s better overall, it would certainly be worse in that it would be missing some key parts of what make this life good.

But maybe this means that I don’t really regret my college decision. Is it really a regret if I wouldn’t do it differently? I think so because, while we say that a regret means that we would do things differently if we could, what we really mean is that we would change only certain parts of what we did and its necessary1 consequences, not that we would redo our entire life from that point onwards. If I say I regret ordering this meal, I mean that I wish that I had ordered a different meal and wish the necessary consequences of that decision were different (the waiter had brought a different meal; I had eaten the different meal), but not that I wish all of the consequences of that decision were different. A necessary consequence of my going to a different university is that I would have been in some more challenging conversations with students and faculty, but it’s not a necessary consequence that I would never meet my wife or have my son. (It’s nearly impossible, but, because I didn’t meet her as an undergrad, it’s not hard to tell a story where we still meet; having this same son is much harder to imagine.) That’s why we can regret but not be willing to do things differently: if, overall, things have gone well, we regret some parts of what we did and maybe some limited consequences of what we did, but not the entire life that came from it.

A bad life, however, might also be one with regrets. But those regrets would be regrets that the person would be willing to wish away if they could. They would take a reroll of the dice from that point on. A tragic decision that colored everything that came afterwards, for example, might be a regret that isn’t part of a good life. It’s a regret that entails that one would in fact like to redo everything, taking a chance that whatever goods there are in this life aren’t enough to make it worth sticking with this one; the alternative would have to be better.

So a good life will have regrets in it, but they’re of the earlier kind: regrets that I would rather keep than turn into a wish to redo things. And a bad life will also have regrets in it: regrets that would be wishes to try again. My own life is mostly of the first kind, a good life with regrets in it that I wouldn’t exchange for a redo. The other regrets that easily come to mind are of opportunities not pursued, of good things I’ll never know if I could have added to a good life, not of tragedies I wish I’d averted. That seems to be the way that regrets can be part of a good life, that we can understand using anticipated regrets to make decisions, and that we still wouldn’t do things differently if we could.

“Necessary” here doesn’t really mean necessary; it means something like highly predictable. It’s no surprise that an ordinary term like “regret” doesn’t actually have logical necessity built into it. But I think it comes close. And, anyway, figuring out which consequences of an action actually “belong to” that action is its own weird topic. ↩