no days off

What is it about achievements that are so important? The philosopher Gwen Bradford proposes that the value of an achievement isn’t in the final product, but in the difficulty we have to overcome to get there. It’s our will we’re praising, not its results.

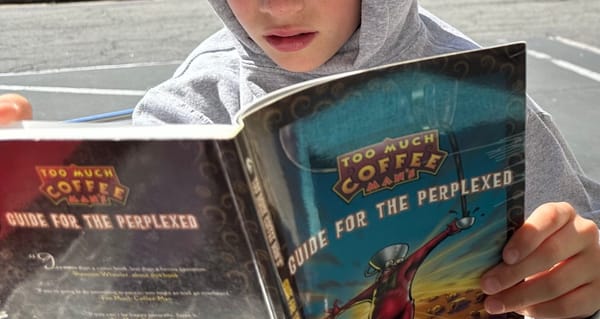

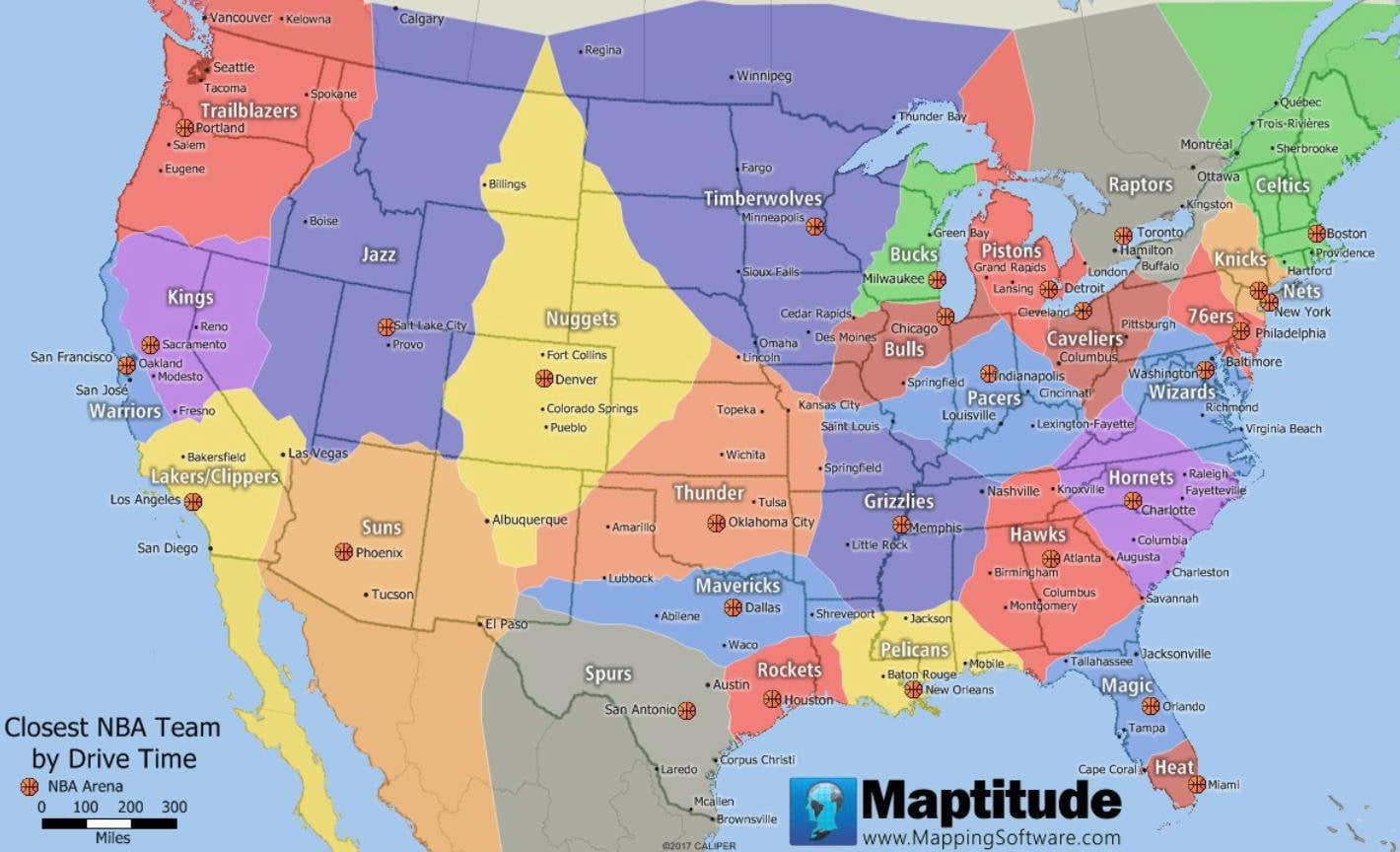

That seems right: if achievements are valuable, then what’s valuable about them is something about the difficulty we have to overcome to get there. My 9-year-old son’s painstakingly hand-drawn map of the US, mapping out which regions he thinks are covered by each NBA team,

is more of an achievement than googling for a similar, pre-made map.

I’m proud of his map, but I’m praising his effort more than the end result.

Not everything that’s hard to do is an achievement. It’s not an achievement for me to get my son to school on time when I’m on my own because, while it’s hard to do, uncommon, and accomplished despite difficulties, it’s not especially praiseworthy. It’s just doing what I’m supposed to do. If I could do it every day of the school year without fail, that would be an achievement and would also be praiseworthy. (One year of grade school, I got a perfect attendance award; never have I won such an award for only one day.) So calling something an achievement does seem to mean that it’s praiseworthy.

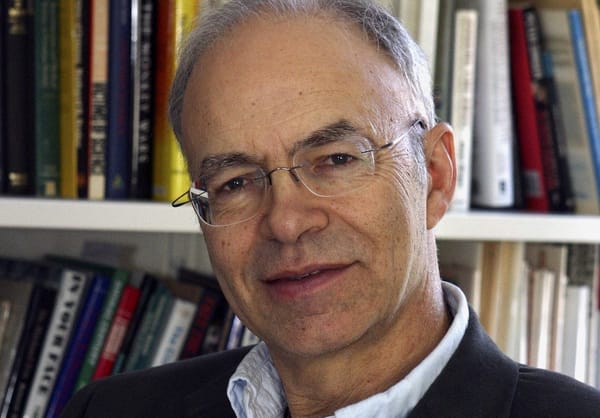

Is living an ethical life an achievement, then? The writer Larissa MacFarquhar wrote a fascinating book about “do-gooders,” people who are extreme in their moral pursuits, often devoting their entire lives to moral pursuits, at great cost. Their moral lives are achievements: they’re uncommon, hard to do, accomplished despite difficulties, and praiseworthy.

For the rest of us, living our ordinary lives, an ethical life isn’t uncommon, or especially hard to do, or accomplished despite difficulty. I’m not even sure if it’s praiseworthy: what would it say about me if I thanked all the people I walked past on the street for not murdering me?

We do praise people who face difficult moral situations, strong temptations or unusual circumstances. But mostly it’s not hard to be moral: I don’t feel tempted to murder when I’m angry, or to steal when I want something I can’t afford. Even if I do feel tempted, it’s a passing thought, not a real temptation. Quitting smoking was an achievement, even if not a moral one, because it was hard to do—though I’d quit enough times before it finally stuck that it wasn’t even that uncommon.

So let’s say there’s a difference between ordinary morality, which isn’t an achievement, and the occasional moral achievements we all have sometimes and the lifetime moral achievements that the do-gooders have. So what? This difference matters because hard cases make bad law, and we get the wrong idea about morality if we think of the achievements as the model of being moral.

Achievements require work, but the work of an achievement is towards some goal. Running isn’t an achievement, but running a marathon is; even running every day is. If I run every day to train for a marathon and then fail to finish the marathon, I didn’t achieve my goal, even if I managed to achieve lots of other things along the way.

Not everything has a goal that’s separate from the actions itself. Running every day is a goal I achieve by running every day. More interestingly, the goal of friendship is being friends, and that’s something you achieve in the very same actions that comprise being friends. If you’re going out for a beer with someone in order to be friends, then you’re overly cynical and/or you’re not friends yet. Once you are friends, then you go out for a beer because you’re friends, not in order to be friends. A marathon is over and done with, but running every day as an achievement isn’t ever done, and achieving friendship and maintaining friendship are the same.

Talking about the goal of ordinary morality is like talking about the goal of running every day or being friends with someone who is already a friend: if it’s a goal, it’s one you achieve by doing what you’re already doing. You make small changes when necessary, but more or less you keep on keeping on. Running and friendship both have many benefits, like longevity and better health and feeling good, but you’re missing the point of friendship if you say that you’re going for a beer with a friend in order to increase your longevity.

It’s the same for morality. For most people, you “achieve” it by doing what you’re ordinarily doing. People sometimes ask what the point of morality is, but not when they’re walking down the street not-murdering and not-stealing. They ask what the point of morality is in hard cases: when they could take a job that will make a ton of money by screwing people over, or when they can ingratiate themselves to one friend by betraying another.1 Most of the time, though, morality is a habit we get into, a pattern of action, an achievement not in general but only when done without exception, in the same way that running every day might be. Mostly, it’s no more praiseworthy than my getting my son to school on time.

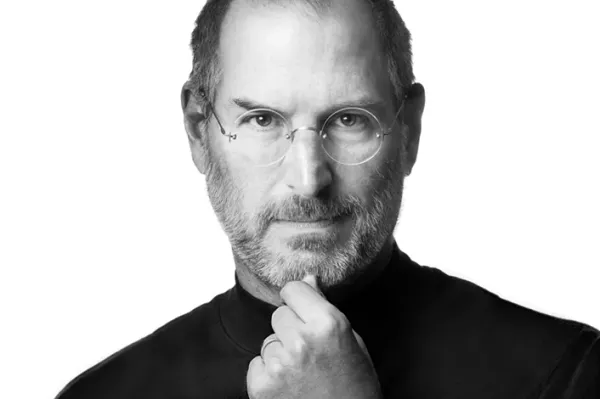

Thinking about morality as an achievement also makes it seem like there’s something beyond itself that it achieves, that there’s some further goal that makes it good. And that actually makes it unclear why we should be moral. If morality is a means to something else, then reach that goal in the most efficient way. If the goal of morality is to increase happiness, for example, and you can increase happiness the most by doing some immoral things, then do the immoral things. MacFarquhar discusses a young man named Aaron, who—like many Effective Altruists—justifies ruining personal relationships while devoted entirely and efficiently to ending the suffering of factory-farmed chickens. If we’re tallying up how much happiness is gained and lost by Aaron’s personal relationships and by the suffering of the chickens he saves, then he achieves more happiness by sacrificing personal relationships; but it’s also clear that the cost of treating personal relationships badly is that he’s being less moral.

If we don’t think of morality as having a goal outside of being moral, then morality isn’t something that can be optimized. It’s something we do, but not generally something we achieve. It has benefits, like friendship and running every day do, but those benefits aren’t the goal of friendship, nor of morality.

If morality isn’t a set of goals to be achieved, then I imagine it’s the way we justify what to do. For example, whatever rules you set for others should be the same rules you set for yourself, and vice versa: view yourself as equal to everyone else unless there’s a reason not to; don’t make yourself the exception. That’s a very basic constraint on almost all thinking. It’s socially valuable, it pushes your reasoning to be consistent, and it looks like lots of traditional golden rules and moral principles. So something like “treat likes alike” is probably a foundational moral principle, and also a foundational logical and mathematical and scientific principle, too.

Reasoning can be better or worse, but reasoning well isn’t something you achieve by doing something else. You can’t skip reasoning well in order to reason better, and you can’t reason better than well. There’s nothing to optimize. You just reason every day, mostly without thinking about what you’re doing or why you’re doing it, and without deserving any special praise for it. Reasoning well and being moral just aren’t that different.

There are lots of reasons that we might have been tempted by the idea that morality is an achievement and something we can optimize. Maybe it’s because we think of everything as a market interaction with tradeoffs that can and should be optimized, or maybe we confuse the goals of collective policies (in which we efficiently maximize happiness for as many people as possible) with the goals of morality (in which we inefficiently don’t). Or maybe it’s shaped by thinking about morally dilemmas and hard cases when we think about morality, instead of thinking about the countless, uninteresting ways that we’re moral all the time.

Regardless, moral achievements for most of us come only from doing something hard, and morality mostly isn’t hard. Resisting temptation can be hard, and never making ourselves an exception to the moral rule is hard. So it’s genuinely hard to take no days off in morality, and that’s an achievement. But, when I say morality isn’t hard, I mean it’s not hard for me, and for most of the people I know. But that’s not true for everyone, not even for everyone I’ve known in my life. But some people are tempted to take a job that will do immoral things to make lots of money; I can imagine a society in which jobs like that don’t exist, don’t pay lots of money, or people don’t feel pressure to take them because enough of their needs are taken care of that they can think about what will make them happy. It would be an achievement if we could make morality even less of an achievement for everyone.

Even when tempted to do wrong, the need to be moral is so great that people rationalize their actions—I’m not stealing: my boss owes me for all the unpaid labor I’ve done over the years—or, worst-case scenario, they redefine morality to fit their actions, declaring, for example, that selfishness is moral. ↩