One more time, without feeling

another shot at understanding meaning without purpose

[The revised and published version of this is here.]

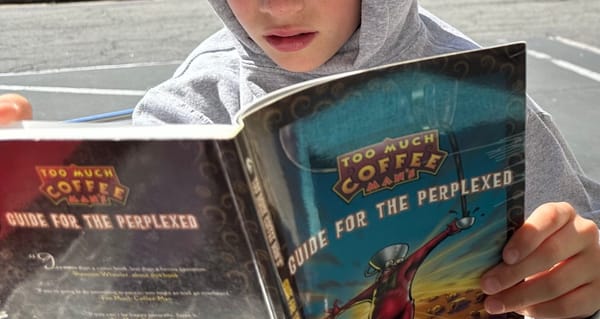

My grandfather wrote music. He was a musician and music teacher for as long as I could remember, but I only ever heard one of his songs, at a Christmas program in grade school. After he died, my musician uncle looked through what, to my young mind, seemed like an entire room of his music and said that it wasn’t particularly good. It was matter-of-fact, not a criticism or with regret or sadness that this is how my grandfather had used his one and only life, writing music that no one would hear, and that the world wouldn’t be any worse for not hearing anyway. It was just a fact. Almost all music that has ever been written isn’t anything special, and this was like most music.

I was about to graduate college when he died, and I still thought my life’s trajectory would lead to recognizable success, probably even some prestige. I wasn’t going to be president (unless the public clambered for it, of course, but even then only reluctantly), but I also didn’t entertain the thought that anyone would someday reflect back on my one and only life and find it lacking recognizable achievements; whatever papers I left behind would be worth looking through.

If there’s one class in which you can expect to ask and answer the question, “What is the meaning of life?”, you would think that it’s a philosophy class. But, in my two and a half decades in philosophy classes, I have never asked or answered that question. I suspect the explanation is sociological. I already read philosophy books with self-help-like titles that make me feel self-conscious in public: In Praise of Failure, Idleness, and How to be Perfect, to pick titles from the past couple of months. The Philosophy section in a bookstore is often next to “Metaphysics” or “Religion.” So philosophers—or at least I—already worry that we’re not distinct enough from these other fields; if we start asking “what does it all mean?”, then what really is the difference? (Why we care that there is a difference is a topic for nearby Psychology.)

Susan Wolf is too self-assured of a philosopher to care where her book, Meaning in Life and Why it Matters, is shelved. Her decidedly philosophical account of meaning is that meaning is found in “loving objects worthy of love and engaging with them in a positive way.” Where we find meaning is different from what meaning is, but her view obviously includes bourgeois meaning: a life reflecting on great literature is meaningful, and a life watching grass grow is not. But what to say about the dilettante and the flaneur? Some of us do what we’re bad at, won’t improve enough to justify life by the improvement, and posthumous success will not be the machina, ex which any meaning will be discovered. Can her account find meaning in my grandfather’s life of writing what no one will hear, or my own of doing the same? Is meaning found in doing things that have no purpose beyond themselves, in loving objects that are not worthy of love?

When someone looks for meaning in life, their search switches almost immediately to its purpose. In fact, in one of the very first instances of the phrase “meaning of life,” in Schopenhauer’s On Human Nature, he immediately follows “What is the meaning of life at all?” with “To what purpose is it played, this farce in which everything that is essential is irrevocably fixed and determined?” (Possibly the first use of “what is the meaning of life?” is immediately followed by “as if there could even be one”: Schopenhauer’s gonna Schopenhauer.)

Meaning and purpose are related, but not synonymous. Purpose has something to do with goals, results, ends, functions; meaning has something to do with how things fit together in larger systems or patterns. Now, one way that things fit together into larger systems or patterns is for each part to have a function or purpose in that system, so having a purpose is one way of having meaning. The hairspring finds its meaning within a watch because its purpose is to provide power to the whole mechanism; its meaning is different if placed in a museum display about the history of miniaturization.

But finding a purpose is not the only way to find meaning. Which is probably good, because purposes are risky when we move from asking about the purpose of a hairspring to asking about the purpose of a human. Grand human purposes have justified almost every historical tragedy: genocides, torture, expulsions, wars. An idle person will disappoint Kant by not developing their innate talents, but slackers don’t incite genocides. The whole point of finding your purpose is to find justifications and motivations to do what you otherwise wouldn’t, and, while I doubt anyone reading this will sponsor a genocide, almost every bad action has at least some justification for it, and working toward a grand purpose makes it easier to find those justifications and dismiss conflicting ones. The bigger the purpose, the bigger the justification, and a purpose-driven life drives roughshod over competing interests.

If we want our lives to be meaningful, though, is there an alternative to finding our purpose? I think there is, and I wonder if the near synonymity of the two terms is itself a historical anomaly.

Google’s ngrams for “meaning” and “purpose” show that usage of the two terms in books moves in lockstep until the mid-18th century, when the use of “purpose” escalates rapidly relative to “meaning” and stays elevated until the 20th century. This is probably not a coincidence. The Industrial Revolution changed far more than what we thought steam could do. It also gave us a watch-like model to understand people and things functioning together, from machines to nations’ comparative advantages. In such a context, a person—like the machines they worked alongside—is whatever their role, their function, their purpose is in the larger whole. And if a growing percentage of the people in society work in roles with clear purposes every day, how could they not come to understand everything and everyone as purpose-guided? The whole world looks like Tetris to me after only half an hour, so what would it look like after a 16-hour shift in the factory?

Of course, the Industrial Revolution didn’t invent means-end reasoning or pursuing goals, both of which are much older than Homo sapiens, and those are the component pieces of pursuing purpose. And cooperation and specialization are inextricable from human civilization. So understanding ourselves as having a purpose did not arise with the spinning jenny. But social conditions shape our self-understanding, so it would in fact be surprising if people didn’t come to see themselves and everyone else on the model of a factory-wide, village-wide, society-wide, even history-wide or universe-wide machine.

Whatever historical change happened might be as difficult for us to reconstruct here and now as it will be for future generations to understand how the world looked in the simple quiet chaos and independence of our pre-internet, pre-cell-phone lives. As Alastair McIntyre has famously explored, telos and ergon in Aristotle’s Nichomachean Ethics are certainly not the “purpose” or “function” of our own conceptual repertoire. But my historical hypothesis distinguishes meaning and purpose enough to clear a path to find meaning without purpose.

We search for meaning more often in a dictionary than in a life. How a word comes to have meaning is, to exaggerate only slightly, the primary topic of 20th century Anglo-American philosophy. Without summarizing, the 20th century philosopher Charles Dodgson (using Lewis Caroll’s plume) can explain in his distinctive way one point of agreement about meaning:

“But,” Alice objected, “‘glory’ doesn’t mean ‘a nice knockdown argument.’”

“When I use a word,” Humpty-Dumpty said in rather a scornful tone, “it means just what I choose it to mean—neither more nor less.”

“The question is,” said Alice, “whether you can make words mean so many different things.”

“The question is,” said Humpty-Dumpty, “which is to be master—that’s all.”

As we’re supposed to realize, contra Humpty-Dumpty, intentions matter, but words’ meanings are found within larger patterns of language and life: patterns of use, of sense, of definitions, of something more than the person’s own mind.

By analogy, the meaning of a life—from the person leading it to the actions and events within it—don’t come from what you privately want them to be. I don’t become a writer by sitting in cafes with a moleskine notebook, and my intention to borrow, not steal, a book is irrelevant if the shelf I’m taking it from is in a bookstore. More dramatically, whether one is a traitor or a revolutionary is not entirely up to them: an action’s meaning, and a life’s meaning, is only partially up to the person doing it.

Now, for something to be meaningful is for it to have a recognizable place in one of those larger patterns. “Meaningful” isn’t “good,” though: borrowing and stealing are both meaningful, as are treasons and revolutions. By contrast, lying on the ground watching grass grow isn’t meaningful because it fits into no obvious social patterns. But even watching grass grow isn’t as far from being meaningful as it might sound: countless suburban dads clearly find watching grass grow to fit their social lives, and we shouldn’t be too dismissive of where to find patterns of meaning.

Now, we might want meaningful lives, but what we really want is for our actions and our lives to matter, to be important. Meaning in Life and Why it Matters, remember? This is where purpose swoops in to make things easy. A recognizable, life-defining purpose organizes your actions into a pattern and shows how that entire pattern matters. Monitoring one’s suburban lawn is meaningful in a way that lying on the ground watching the grass is not, but neither matter. (You, like my neighbors, might disagree.) But if that nice lawn is the outfield for the World Series? Or the only outdoor play space for The Little School for Refugee Children? A good purpose makes patterns meaningful and explains why they matter. That’s why “finding your purpose” is a cure-all to a lack of meaning and mattering.

So what’s the alternative? The alternative is to find meaningful patterns that are not purpose driven but still matter: having friends, having fun, being nice, being generous, loving one’s family, having hobbies, being happy, contemplating God. If we insist on finding a purpose for everything, we can find them in that list, too, but we’re overreading those patterns if we do. They’re meaningful and matter even without any larger purpose. There needn’t be a purpose to having and sustaining friendships, and the purpose of a vacation needn’t be to “recharge” for more productive work. Enjoying life also matters.

I don’t want to insist on a false dichotomy. Purposes in life are good, too. Achievements are nice. It’s no coincidence that society has arranged itself in such a way that people find their purposes in ways that make it easy for us to get good food and enjoy air conditioning, and it feels good to contribute to society, even if only on the margins. But we’re past the point that civilization needs people to find a calling and live with passion. Many are called, but few are actually needed, and you don’t need to feel a lack if you’re not one of the elect. The rest of us can help where needed, but should also learn how to appreciate non-instrumental leisure, friendship, and play. We needn’t give over our whole lives to a purpose in order to find it meaningful.

But do our purpose-less lives matter? Does writing little ditties, musical or philosophical, matter? Maybe, because, unlike meaning, whether something matters can be determined entirely by what’s in someone’s head: something matters because it matters to me. Or maybe not: maybe watching grass grow and writing down one’s philosophical thoughts simply doesn’t matter, no matter what anyone thinks. I’m not sure.

But maybe what is meaningful in a life of writing ditties that don’t matter isn’t the ditties, it’s the writing of them. Writing is a way of expressing one’s creativity or intellect, even if the creativity and intellect are weak. It’s the human expression that’s meaningful—we all recognize the pattern of writing and composing—and there is a strong case to be made that humans’ expressing their creativity and intellect also matters. Not, as Kant would have it, because we’re developing those faculties, though that might be true, but because those meaningful, purposeless patterns are themselves constitutive of a worthwhile life. We see that more clearly if we ask not what a person is for, but, instead, how to love the worthiness of what we simply are.