the asshole and the hiding hand

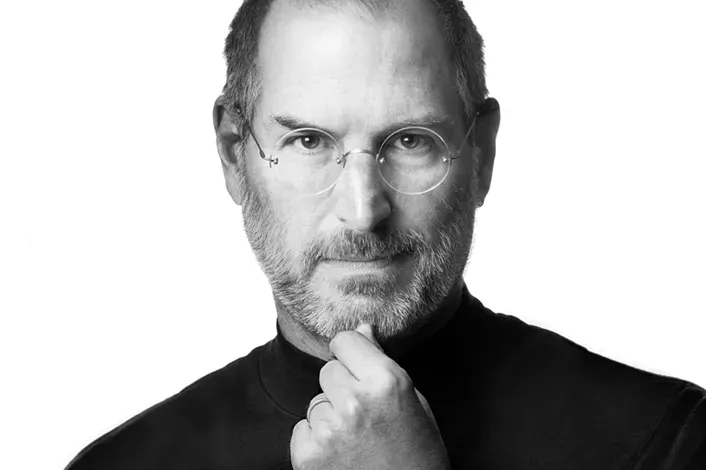

I'm rereading Walter Isaacson's biography of Steve Jobs, who is the model of the kind of asshole that I'm interested in because he undeniably did some world-changing great things and was undeniably an asshole, and almost certainly did some of the world-changing great things because he was an asshole.

Whether he could have done different, but equally great things by not being an asshole is a great question that quietly wanders throughout the book, when there are glimpses of alternatives that might have been just as good, maybe even better--but unpredictably so--and maybe worse. Steve Wozniak wanted to make Apple computers open and the designs free: that would have kept Apple from turning into a hugely successful company, but it's impossible to know what that would have led to, how many hobbyists might have come up with their own ideas, different but not worse.

This reminds me of what Lebron James said in his ad about his background, coming from humble beginnings: "You know what would be really special? If there were no more humble beginnings." It's amazing that Steve Jobs could make so much great tech, but he also perpetuated a system where it's a challenge to make great tech.

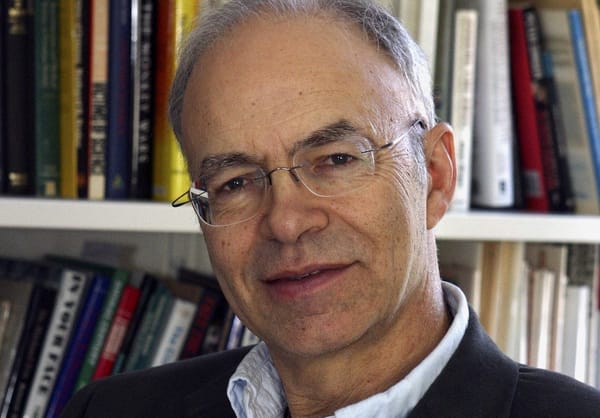

The question here that I'm wondering about, though, is how Jobs's asshole behavior reflects Albert O. Hirschman's principle of the hiding hand. Hirschman's idea is that, because you can't predict creativity and how you'll be able to solve problems, sometimes you can only employ your creativity and solve big problems by underestimating those problems. Having underestimated the problems and, as a result, having committed to build whatever you're going to build (a paper mill in Hirschman's opening example), you then discover or create new solutions to the new problems that you discover. If you hadn't been so naive in your initial estimate of the problems you would face, you never would have started the project, and thus never would have discovered how to solve the problems.

Hirschman presents this as a principle--even capitalizing "Hiding Hand" to make its Principle-ness clear--but it's really less a principle than an observation: some projects are able to find creative ways around unforeseen problems that, if seen, might have been enough to stop their naive quests before they even started. Of course, some projects don't find creative ways around them, and there's no way to know the difference at the outset, so that's why it's less a principle than an observation that some survivors survived.

There are a few examples of this from the Isaacson book. The example that I just read is when Jobs says that the Mac software has to be ready to ship by a deadline that he's told by the engineers is too soon. They ask for a two-week delay; Jobs tells them that they can't have it. He inspires and/or demands them to work to make the deadline, and they do.

Maybe the engineers and programmers asked for the extended deadline not because they thought it was impossible to finish by the original deadline, but because they thought it was impossible while also getting to sleep at home in their beds at night, and, while they were clearly inspired and dedicated, they also didn't think it was worth working literally around the clock for a deadline that could simply be moved back by a couple of weeks with no costs other than the reputational costs to their megalomaniacal boss. That's how I imagine the story.

Or, to fit the principle (the "Principle"), maybe they asked for the extension because they thought it was literally impossible to finish on time, regardless of how much they worked. And when told that they had to, they then discovered creative ways that they could. That's the hiding hand story, and that's obviously the story that the hard-driving task master would like to believe.

Maybe it's an inspirational story: that's how it was written, though the story is in a book about Jobs, not a book about an engineer who didn't sleep for two weeks and whose name isn't even in this book. But what makes the story a story of Jobs's being an asshole is that, after he inspires them, and they discover in themselves the ability to finish by the deadline, the story continues: one of them goes home and sleeps for 6 hours, then comes back to the office, and Jobs (who was obviously feeling his own deadlines) then demands they start working on the very next, compressed deadline. He displays a psychopath's indifference to using people for his own ends. That's the real asshole part of the story.

On rereading, Jobs is more of a visionary salesman than I remember. This impression might also come from my having read Isaacson's biography of Elon Musk since I first read the Jobs biography. Musk gets rich despite his lack of programming ability or technological insight or management ingenuity, and becomes a successful celebrity investor who thinks of himself as an engineer, so I'm now seeing elements of that same charlatan story in Jobs--though the differences are pretty dramatic, too. Regardless, the stories are impressive of how Jobs can sell people, even if Isaacson doesn't describe in detail how he does it. But people across the book think that Jobs's "reality distortion field" is not just his lying to others but his lying to himself about what's possible (or good?), and somehow that lying and persuasion are part of the same talent.