what my son has actually learned from sports

you can't work hard enough to become the coach's son

In the last couple of years of watching my son play organized baseball, basketball, soccer, fencing, and tennis, plus all the disorganized and improvised sports that he plays at every opportunity, I’ve had a lot of time to think about why we spend so much time on this. While standing around with other parents, I’ve exchanged many platitudes about the value of sports, especially for kids. Some of them are accurate. For example, it’s good for kids to deal with failure and loss in a supervised and limited way. Losing gives you a chance to learn how to recover from it, lessons about what to improve the next time, and experience balancing the pain of the loss against the feelings of good things in life. I’m sure I’m only a quick search away from a dozen good articles along the lines of “what I’ve learned from Little League.”

But I’ve also been thinking about the other lessons that he’s learning, the ones that I find it more awkward to talk about. For example, one of them just came up last week. He was playing on a team at a basketball camp that assigned kids to teams without tryouts, and they started playing against other teams on the first day, which means the teams were unbalanced and the coach didn’t even get much of a chance to figure out lineups. His team wasn’t very good, which led to a lot of frustration and sadness. We talked some general strategy: when to shoot even if your teammates want a pass, and when to pass even if you might have a good shot. But the biggest thing we talked about was when to be frustrated and sad.

This is an ongoing conversation. During a little league game a couple of years ago, he was sad towards the end of the game because it looked like they were going to lose. And I told him that the time to be sad is after the game is over, and that as long as the game is going on you should cheer for your teammates. The lesson about not giving up is a standard one, especially in baseball where, without a timer and run limit, hope only ends when the game is literally over. But the lesson about when to be sad is a harder one to get across.

I know the way I grew up, you’re not supposed to be sad at all. You can be disappointed, which is more cognitive—you failed to reach your expectations—but not sad. Maybe this isn’t entirely true: I wasn’t allowed to play any organized sports, so I don’t know what coaches said when the team lost. But I know what adults in my small town in Kansas said, and it wasn’t anything close to “go ahead and let those feelings all out.”

By contrast, I want my son to be sad sometimes. It’s a good emotion to have, and if you don’t learn to have it at the right time, then you end up feeling other emotions instead, like anger and frustration, when really you should just be sad. So it’s an important one. But it’s also important not to give up in the middle of a game, even if it’s clear well before the end of the game that your team is going to lose. So what I’ve settled on as the lesson is the one I told him about baseball: the time to be sad is at the end. Until then, you push, even when it’s futile. Then, when it’s all over, you can be sad. That’s a lesson he’s not picking up on his own, but I’m definitely pushing it on him.

A corollary of this: no complaining during the game unless it’s actually going to make a difference. If you think complaining about a call is going to change that call or even make the ref change a future call, then sure. But no complaining about how things aren’t going your way. After the game, it can be part of figuring out what to do in a future game. But not during the game. No complaining then.

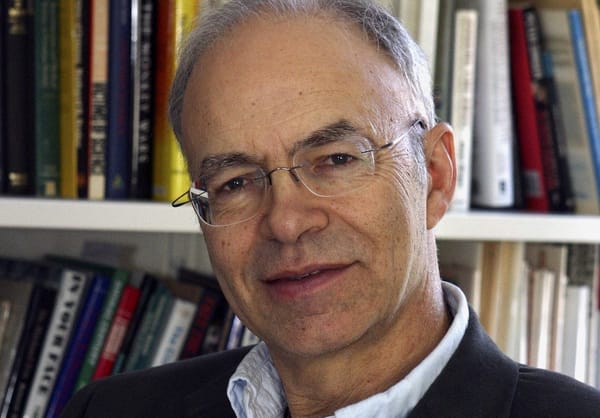

Those are pieces of advice that I’m explicitly giving him that I hope he’ll remember, eventually. He’s 10, and it’s very unpredictable what he’ll remember. He might not remember a lesson I spend five minutes telling him, but he’ll remember an offhand comment I make to someone and will bring it up every few days for weeks.

But I think the lessons that he’s learning are mostly not the ones I’m teaching him. I think he’s mostly learning by observing. And that’s been more interesting, since he filters those observations through me, and I only have a few seconds sometimes to shape his observation before it gets locked in. So I’ve spent a while thinking about these so I’ll have things to say if I need to.

One is: the coach’s kid gets priority. One of his first ever coaches took this to an extreme, and started his kid on the all-star team though it was obvious to everyone else that he shouldn’t have been on the team at all, and the very talented catcher who loved practicing that position and played it incredibly well spent far too much time on the bench. My son understood perfectly why the coach’s kid was playing.

The less obvious cases of this happen all the time, and I think they’re for perfectly good reasons: coaches know the demonstrated performances of the kids on the team, but they know the possibilities of their own kids. It reminds me of the strategy laid out in Moneyball of picking players based on demonstrated performance rather than observed talent. Coaches, like talent scouts, see the talent in their own kids, which might lead them to overestimate their abilities, while they only see the performance in most other kids. So it’s not that they’re biased, exactly, but they have a different, deeper, but maybe misleading understanding of their own kids. But what it looks like is that the coach’s kid always gets to pitch, regardless of how well they pitch.

This is actually a more general lesson: coaches are sometimes wrong, and they get to make decisions that affect you anyway. This has been a hard one to talk about, and it goes along with understanding that adults know less than you think. A coach, years ago, kept widening and widening my son’s batting stance, hoping to help him get out of an ever longer hitting slump, and, as soon as the season was over and we had time to go to a real hitting instructor, that instructor immediately told him that he needed a narrow stance, and the wide stance was hurting him by changing his height too much during the swing. He didn’t know any better, and neither did I. (Again, I didn’t play organized sports growing up. I’ll never be a good coach for any sport at any age above 5.) My son had been frustrated that his hitting wasn’t improving, but he did what he was told, failed to hit, and that coach is probably still telling kids who aren’t hitting well to widen their stances.

What makes it frustrating, though, is that sometimes you know that you’re doing what you’re doing only because the coach says so, but it’s possible that no one will really appreciate how well you’re playing. A team’s lineup makes a huge difference in basketball, and a player who looks very talented in one lineup will look ineffective in another. But to those of us who don’t understand the team and strategy, we only see that a player is getting lots of points or rebounds, not all the rest of the action that sets that player up. And you can’t complain about it for fear of sounding like a whiny kvetch making excuses. So you play (or not) and try your hardest (or not), and maybe someone can tell how much of your success (or not) is because of you and how much is because of the coach, but mostly not.

So, if you can’t count on success, what can you do? Here, I feel confident in what he’s learned: if you work hard, you’ll improve; and other people, regardless of how much they have worked, might be just as good, or better. This is the truest meritocratic lesson. My son has improved significantly at all the things he’s worked at in sports—though the things he chose to work at were mostly things that he showed some ability in already. His shooting and dribbling are way better than I ever expected they would be; his hitting has improved in baseball and tennis; and his pitching has stalled out now that he stopped working on it.

I told him a white lie when he was young. I told him that his special talent is that he can improve by working hard. It’s only a white lie because he does seem to improve quickly when he works. But everyone improves by working, hence the lie part of it. But the lesson isn’t that if you work hard you’ll succeed: that’s just propaganda that gets workers to accept being exploited. Rather, if you work hard, you will get better. Your being better might not make you good enough. And you might also be good enough without working hard. The only lesson is about how to improve, not about how to be successful. Because no amount of work will get you to be the coach’s son.

Or to be lucky. And that’s the final lesson, and one we talk about all the time: you can’t win without luck. Sometimes it’s the luck of who your parent is, and sometimes it’s the luck of a bad bounce or a 1 cm deflection, or a good bounce and the tiniest bit of randomness that goes in your favor. The better you are, the less of a role luck will play, but it always, always plays a role. Injuries are the greatest example of luck, but so are genetics. So, when the game is over, you can be happy or sad, you can complain (quietly, to me) about the coach or the players or the weather or the ump, you can decide what to work on for next time, but we always talk about the sheer luck of all of it.