why platitudes?

Kate Bowler wrote a best-selling memoir of her young diagnosis of and treatment for cancer called Everything Happens for a Reason (And Other Lies I’ve Loved). I read it when I had a similar cancer diagnosis, though I’d heard of the book (and loved the title) before that. And I read her sequel to the book, which covered the same material again with a little more polish. I liked both of them. And then, to share how much I liked the books with someone else, I went to find a quote that captured what I liked about them, and I realized that there was nothing I could pull out that stood on its own as especially meaningful.

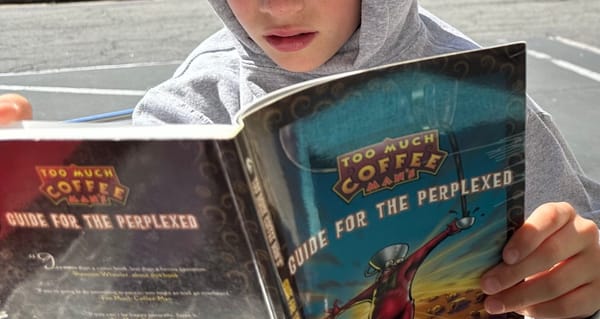

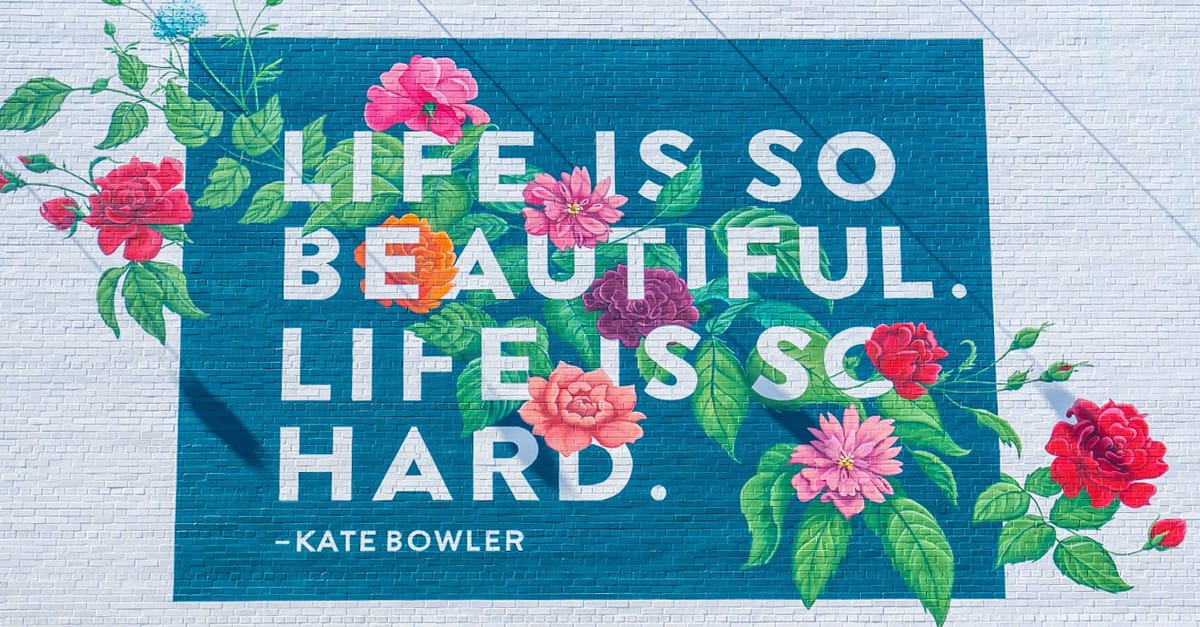

What I could pull out of the books were, instead, once removed, just platitudes, empty phrases like “Life is so beautiful. Life is so hard.” Platitudes definitely speak to people—that particular one is now a mural—but, divorced from the stories they were in, they’re empty and all but meaningless. Life is beautiful? Life is hard? As the conclusion of a long story about handling an uncertain cancer diagnosis or as the title of a holocaust film, those feel weighty, but pulled out of context and presented on their own? What does “life is beautiful” say that you don’t already know?

An existentialist philosophy professor at a former department, at the end of a long lecture, paused for very dramatic effect before revealing her core insight from this particular lecture. She said, with deep affect: “Life… is… hard.” It seemed ridiculous, even to the students (who talked about it later), the dramatic buildup for the vacuous payoff. In the professor’s mind, I imagine the students were sitting breathlessly, pencils poised, waiting for the secret of the universe to be revealed; but, of course, we always imagine students are hanging on our phrases, even though we also regularly tell them things like, “That was important. You should write that down,” which suggests that we know they’re barely hanging on the phrases we want them to hang on. “Life is hard” can emerge from some hard won insights, but the phrase itself doesn’t need to be written down to remember the insights.

It was thinking about how these books both felt insightful and didn’t seem to have any insights that made me write “What I’ve Learned From Having Cancer is Nothing.” I stand by what I wrote there: cancer didn’t give me insights. Maybe that’s on me, but I explained there why I think that is.

My point there was that not everything that is meaningful feels meaningful. What it is for something to be meaningful is for it to be connected to something larger, something important. Going for a walk mostly isn’t meaningful, but being a daily walker is, and maybe so is doing a Walk for the Cure. Those are larger (literally or symbolically) than a single walk. Mostly, we don’t realize how meaningful our ordinary actions are because we don’t reflect on them much as anything larger.

On the other hand, not everything that feels meaningful is meaningful. Watching the sun rise in a clearing in the mountains or over the ocean might feel epic. Not much is bigger or more important, for humans, than seeing the cosmos on display, so it feels meaningful because it’s something vastly larger than ourselves. But the person watching the sunrise is part of the cosmos in only a trivial way: the cosmos is indifferent to us, and we’re not contributing to the sunrise at all. So it feels meaningful to watch the cosmic display, but we’re not any part of it. Or perhaps the indifference of the cosmos to our own lives is what feels meaningful? We do, perversely, make up part of what the universe is indifferent to—maybe our tininess and insignificance is what people are feeling in that situation.

Lots of things are bigger than us, and we can feel ourselves as part of them. Maybe this is why religious beliefs make ordinary lives feel meaningful: my little actions are part of this bigger community or divine plan. Birth, death, family, and religion can make most anything feel meaningful since it’s so easy to find ways to connect whatever is happening to them, and they’re bigger. Abstract ideas like friendship and loyalty and perseverance are all big and potentially meaningful if we find ways our life has something to do with them. Sometimes what feels meaningful even is meaningful.

What I wonder, though, is why platitudes feel meaningful. What are they connecting to that is larger than oneself? I agree that “life is beautiful” is larger than oneself, but how does one connect to that sentence in a way that makes it special? Does it prompt me to think about things in my life that are beautiful, which then prompts me to understand some larger pattern of beauty in my life?

Maybe that’s my objection. If the simple sentence “life is beautiful” prompts you to see beauty in your life that you weren’t already seeing, I wonder why you weren’t seeing it before and why it took basically nothing to make you see it. The sentence didn’t point out something beautiful that you hadn’t noticed before or reframe what you were seeing. It didn’t point out a whole pattern where you’d been ignoring one. It’s a sentence to nod along to, but it doesn’t add anything to what you already understand. My objection is like the one I heard years ago in a review of the movie The Truman Show: it’s a fun movie, but if it makes you think, you need to get out more. If “Life is beautiful” makes you appreciate the beauty of life, then you’re going to love all the new thoughts you’ll have when you let your mind wander a little.

Even if the sentence does prompt you to see beauty in the world, would that make you find that sentence itself meaningful? The sentence isn’t a particularly special way to get to that thought. The philosopher G.E. Moore’s article “Proof of an External World” “proves” that there is an external world by pointing out that Moore has two hands, which are objects in the external world, so there’s an external world with objects in it. Whatever we think of his argument, his assertion that he has two hands isn’t a special way to get to that conclusion. There are lots of things, like hands and feet and tables and giraffes, in the external world. That’s his point. It’s an engaging argument, but he’s pointing out the obvious in a way that makes us realize that we were looking for a proof that we didn’t in fact need. You’re not supposed to read Moore’s article and find the obvious parts insightful and then feel inspired to paint “Here is one hand… and here is another. -G.E. Moore” on a wall.

By contrast, if something unexpected or idiosyncratic makes me realize the beauty of life, then maybe it takes on some significance. If a rock reminds me of the kind of rocks that my son used to collect when he was the little kid who used to come home with pockets filled with them, then that rock itself might take on some significance. It won’t be meaningful to anyone else—it’s still just a rock—but it might become meaningful to me, and I could even imagine using it as a memento to remind myself of his youth, or how quickly time passes.

So maybe that’s what’s difficult to understand about a platitude like “life is so beautiful”: I don’t understand how it prompts anyone to have an insight that they didn’t already have; and, even if it does, I don’t know why the sentence gets any special credit for the insight. Within the context of the book, it feels significant (though I think death makes things feel significant even when they’re not; that’s another topic), but I don’t see how any of the specialness remains when painted on a wall.

All that said, now that the sentences are painted on a wall, I suppose someone reading it will look for some special, deeper meaning, something more than the platitude that it is, which could lead the person to find something even deeper there. So maybe it becomes meaningful going forward in virtue of being presented as meaningful already, even if not to someone uncreative like me who refuses to look to the sides of buildings for meaning.